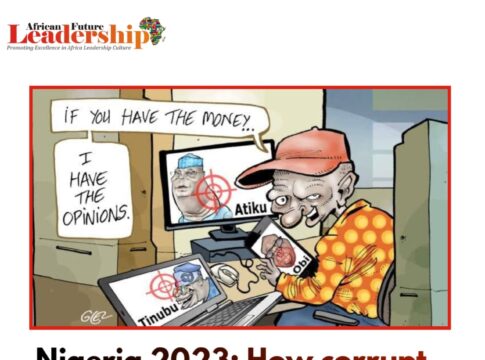

A ‘BBC’ investigation has revealed that Nigerian politicians in the middle of a campaign are using the digital services of whistleblowers, sometimes resorting to disinformation.

At the time of mortifying and propagandist “ism” ideologies, the 20th century seemed to have given way to a 21st century of deciphering objective information and popular education. But the advent of digital technology, which was supposed to guarantee popularisation and transparency, is also synonymous with “news” that is as viral and monetised as it is unapproved, or even “fake

With five weeks to go before the presidential, legislative and senatorial elections on 25 February, many Nigerian politicians have no qualms about riding the wave of “alternative truths”.

Wave of disinformation

This is what a BBC investigation revealed.

The British public service broadcaster showed that Nigerian political parties pay, under the table, influencers to orient their opinions, or even to order disinformation content on their opponents.

READ MORE: Ortom’s convoy was involved in a car accident, lawmakers injured

The stakes are high. 80 million Nigerians are connected to social media where informal opinion leaders are active, some of them with hundreds of thousands of followers, especially on Facebook and Twitter. And the most viral of their publications continue their little way, especially on WhatsApp.

Reaping the rewards

The rewards offered to influencers and their networks of “micro-influencers” are such that the purchase of consciousness quickly turns into intoxication:

Cash sums of over N10m (over $16,000);

Sumptuous gifts;

Government contracts;

Political appointments as assistants or on boards of directors.

Fake news stories are often rooted in religious, ethnic, or regional controversy.

Kashim Shettima, the APC’s vice-presidential candidate, was unfairly linked to members of the Islamist group Boko Haram, and Peter Obi, the Labour Party’s presidential candidate, to the separatist movement Ipob (Indigenous People of Biafra). The PDP presidential candidate, Atiku Abubakar, will be given an imaginary medical file.

Admitting to practising disinformation as a “game” whose score is the number of subscribers and views, the launchers of false alarms favour the dissemination of viral emotion, taking advantage of this ambient irrationality that is neither specifically Nigerian nor exclusively African.

The battle of the trolls is also raging in French-speaking countries where France and Russia are in trouble. Outside the continent, political fake news has plagued democratic events such as the 2016 US presidential election or the Brexit vote.